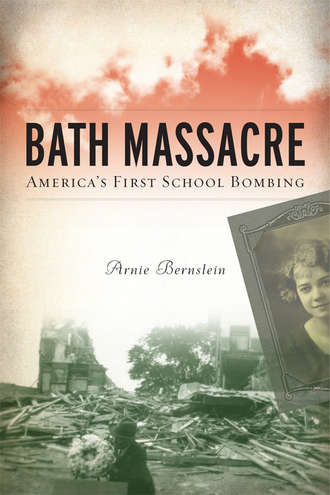

Arnie Bernstein is a Chicago author who wrote a book about a crime whose effects are near and dear to my heart: the 1927 bombing of the Bath Consolidated School building in Bath Michigan. The event—which to this day remains the worst school-related mass murder in the nation’s history—was carried out by a disgruntled local farmer named Andrew Kehoe, who riddled the school with explosives and killed 45 people (and injured 58 others) over slights he believed he had suffered at the hands of fellow community members. For more detailed information about the crime, please see my previous post: The Bath School Disaster

The crime especially resonates with me because I live about ten minutes from where it occurred. Consequently, when Bernstein’s book, Bath Massacre: America’s First School Bombing, was published in 2009, I made sure to buy a copy right away. The book provides a gripping look into a crime that has essentially been relegated to the footnotes of history. Through Bernstein’s prose, the people of Bath come alive, as does the man whose actions would shatter their lives forever.

How did you hear about the Bath School Disaster and what prompted you to write a book about it?

My first three books were history/guidebooks on various aspects of Chicago, where I live (Hollywood on Lake Michigan, about Chicago’s filmmaking history; The Hoofs and Guns of the Storm, about Chicago’s Civil War/Abraham Lincoln connections; and The Movies Are: Carl Sandburg’s Film Reviews & Essays, a compilation of work by Sandburg, who was a film critic for the now-defunct Chicago Daily News in the 1920s). I wanted to do a full-blown narrative nonfiction book, my favorite kind of reading. I think my career has been based on writing the kind of books I would like to read myself! I didn’t really have a set plan on what I wanted to write, other than I wanted it to be a story that somehow or other had slipped through the cracks of history. I really like that kind of material.

One of my favorite websites is Find a Grave, which is a wonderful catalog of famous necropolises, burial sites of notable individuals, literally thousands of other cemeteries and graves worldwide. One day I was looking at the site and saw something about a memorial to the Bath School bombing of 1927—something I’d never heard about. The story hit me hard. I knew I had to write about it.

What sources did you consult for your research? Are survivors of the disaster still alive, and were you able to talk to any of them?

My sources were multifaceted. There was a previous history about the bombing that was published in 1992. Another book was produced in the months following the crime called The Bath School Disaster by Monty Ellsworth. Ellsworth was a Bath resident who lived across the road from Kehoe and knew the man. The book was both a memorial to all the children and adults murdered in the explosion, as well as an account of the day’s events, with some background history of Kehoe. Ellsworth sold this book to the many people who came to the town in the summer of 1927 to see the ruins of the school and Kehoe’s farm. There was also a town history that chronicled Bath from its founding to the 1970s, when the book was published. That was wonderful for background information and helping to create a sense of what this town meant to the families that have lived there for generations.

I relied heavily on newspaper accounts of the story and its aftermath, including The Lansing State Journal, The Chicago Tribune, The New York Times, and others. An inquest was held the week after the bombing by local authorities, a sort of legal hearing to get to the bottom of how the day unfolded from beginning to end, and Kehoe’s behavior in the weeks and months leading up to the crime. The transcript of that inquest was invaluable. It gave me scenes, dialog, internal musings, and other basics of nonfiction storytelling that were all incorporated into the book. Other sources included school board meeting notes (Kehoe was the board trustee), plus various newspaper and television stories about the bombing that were done over the years. There’s also a few websites with information about the crime.

One of the most important aspects to my research was the footwork; going to Bath, walking around the site of the former school which is now a memorial park, the main street where many of the buildings I wrote about still stand, and, of course, the cemetery where 17 of the children and a few of the adults are buried. The elementary school also has a museum filled with artifacts and photos from the school, not just from the bombing, but also the history of the Bath school system in general. Museums are always a wonderful resource for nonfiction writing and something as specialized as the Bath School Museum is a researcher’s dream.

Some survivors, who had passed years ago, had written their accounts of the story. I spoke with children and grandchildren of survivors, people who live with the shadow of May 18, 1927 looming large throughout their lives. These voices were powerful and profound. I was fortunate to interview four survivors. These interviews were the real heart of the book. One of the people I spoke with was in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. Though he had trouble with everyday things, when asked about May 18, 1927, he knew what he was talking about. His brother was one of the many children killed in the bombing. His sisters were eyewitnesses to one of the climactic moments of the day, with a story that is riveting. Josephine Cushman Vail was another survivor I spoke with; she was 14 years old in 1927 and not in the school building at the time of the explosion. Her little brother Ralph, who was 7, was killed. She told me everything she remembered, clear as day. At first I was a little nervous as she started telling me some of the gorier moments, including what her brother’s body looked like when she finally saw him in the temporary morgue. She was 94 when I interviewed her, and I didn’t want to upset her. At one point I said, “Josephine, you don’t have to tell me so much.” She responded that no, she wanted to tell me everything. “I won’t be around forever and I want people to know what happened.” Some of the things she said were gruesome and graphic; all that went into the book, as it should be. Josephine and I ended up having a wonderful friendship. She died a couple of years ago, just a few weeks after her 100th birthday. I still miss her!

Interestingly, after the book came out, I was contacted by a few survivors who’d long since moved out of the area. One lived in Canada, another in Nebraska. I interviewed them and gave the recordings to the Bath School Museum. This is a story that does not end.

What effect did the process of researching and writing this book have on you?

My original intent was to write a good story. But during my first visit to Bath, as I walked through Pleasant Hill Cemetery looking at the graves of 17 of the children killed that day, I realized this was not “my story” or “my book.” I realized I had to honor the victims as best I could. So I did my damnedest and I’d like to think I succeeded. Throughout my work on the book I kept a picture on my desk, a photograph of a memorial plaque that has all the victims’ names on its face. That was why I was writing the book and it was important to have that with me every day.

I’ve been told by several people in Bath that the book has gotten people talking about what happened. Keep in mind, for many years we lived in a society where we simply didn’t talk about anything so horrifying, be it a mass murder or the Holocaust. But talking is good, as we’ve learned over the years. It’s important to keep these things in mind, to bear witness to those who’ve gone before us in ways that are beyond the scope of imagination.

Another thing I’ve worked hard at is to change the nature of how the story is discussed. One thing that bothered me when I first started researching was that May 18, 1927 was continually referred to as “the Bath School disaster.” That wasn’t right. A disaster is a random and unpredictable event or accident, be it a car crash, tornado, fire, or something along those lines. What Kehoe did was deliberate and calculated. It was a crime in the truest sense of the term, and I wanted that to be clear. Hence, I took to always referring to what happened as “the Bath School bombing.” Since the book was published in 2009, I’ve noticed the terminology has been changing. That’s good. It’s another way to honor those who were killed. They were murdered, plain and simple. Maybe I’m doing what Josephine said she wanted, to make sure people know what happened that day.

What happened in Bath was the first mass killing of students in a school, a crime that has become horrifyingly common in our times. Columbine in 1999, Virginia Tech in 2007, Sandy Hook in 2012, Umpqua Community College just a few months ago. And so many others. (And that doesn’t include things like the shootings in shopping malls and movie theaters and work places.) Having written a book on the first mass killing of school children, I’ve become an inadvertent expert on this subject. On December 14, 2012, when I first heard about Sandy Hook, my initial reaction was “Omigod, not again.” My second thought was, “I think I’m going to be busy.” I wasn’t wrong. The phone calls started that afternoon. In the week that followed I was interviewed by radio, television, newspapers throughout Michigan and other states, and even by an Australian radio station. News outlets wanted a different angle on the story, and the Bath School bombing did make sense in that respect, in that both in Bath and Newtown the victims were largely little children, kids in kindergarten, first, and second grade. There’s even a parallel between Vicky De Soto, the teacher who was killed as she protected her students at Sandy Hook, and Hazel Weatherby, one of the teachers killed in the Bath explosion. When they found her in the rubble, she was barely alive and was cradling two children, one in each arm. Her teacher instincts must have kicked in when the school collapsed and she probably reached out to protect her students. Once the rescuers took the children from Miss Weatherby’s arms, she gave in to death. She and Ms. De Soto are kindred spirits in a sense, linked through the decades by their courage and devotion to their students.

These interviews took a toll on me; I finally had to call my rabbi for some advice on how to cope. It’s tough stuff, being a spokesperson for two generations of murdered children. And then there’s this ironic twist of fate. It turned out that I knew a minister in Connecticut who lived just four miles from Sandy Hook. She was one of the many people called into service the day of the shooting, and was in the firehouse when they told the parents that their kids wouldn’t be coming home. I realized I was the connection between two towns that were thrust into unimaginable horror. I called friends in Bath that afternoon, and asked if perhaps they could write a letter to the people in Newtown, saying “we have been there and we are with you.” The Bath School Museum committee penned a beautiful letter, which was published in the Newtown paper. My minister friend responded with a lovely “thank you” to the people of Bath. The following May, I was at the annual Bath School reunion luncheon, which they hold on the Saturday closest to the commemoration of the bombing. Both letters were read to the gathering. Trust me, there wasn’t a dry eye in the house. I don’t want to take any undue credit for this; these letters were written by and for those who could understand in a way only survivors can. But arranging for this is probably the best thing I’ve ever done with my life.

Andrew Kehoe left behind a message on a sign that crews found at his farm after the disaster: “Criminals are made, not born.” In his case, do you believe that’s true? Certainly he bears complete responsibility for his acts, but do you think that, had things gone differently for him in life, Kehoe would have resorted to murder? Or did he use his misfortunes simply as an excuse to commit a crime that was already innate in him?

The most difficult aspect of writing this book was trying to drill inside Kehoe’s head and get to the “why” of the crime. At the end of the day, I realized there is no “why.” He was a classic psychopath, able to connect with society on one level while on another level he nursed demons within and kept them hidden in plain sight. The frustrating part of this crime—as it is with modern-day mass murderers—is that the “why” is known only to the killer. The overwhelming majority of people understand that killing others in spectacular, well-planned acts of violence is evil. Kehoe didn’t have that switch in his head. It’s that simple and that frustrating, because as rational beings we want to know the “why” behind any crime. What was the killer’s motivation? Part of the mythology that’s surrounded Kehoe over the years is that he committed the crime because he felt he was being financially ruined by the taxes he paid to keep the school running. That’s simply not so. I don’t know anyone who likes paying property taxes, but we don’t respond by lacing the basement of the local school with an intricate system of wires and dynamite, kill little children, and blow ourselves up like Kehoe did. That is part of the madness of the man. One of the resources I used to explain Kehoe’s actions (such that they can be explained) was Clarence Darrow’s defense of Leopold and Loeb after they murdered Bobby Franks in Chicago in 1924, three years before Kehoe’s crime. In his plea to save these two admitted murderers from the death penalty, Darrow implored the judge that there was no reason we could understand why Leopold and Loeb did what they did. It was something that was innate to their nature. That’s frightening to consider, but Darrow was right. It sheds light on the dark processes of an unsound mind that could conceive and carry out such crimes. In that sense, the Bath School bombing, Oklahoma City, Columbine, Sandy Hook, the recent shooting in Oregon, even 9/11, all have this terrible element in common. There are monsters among us, neighbors like Kehoe, schoolmates like Harris and Klebold, Army veterans like McVeigh, fellow passengers on an airplane like the 9/11 hijackers. As Darrow said, in the making of the man or the boy something slipped. That’s a hard fact for us to wrap our minds around, but it’s the cold, hard reality.

After Bath Massacre, you wrote Swastika Nation: Fritz Kuhn and the Rise and Fall of the German-American Bund, a book about an American pro-Nazi movement in the late 1930s and their leader who tried to establish a fascist movement in the United States (St. Martin’s Press, 2013/Picador, 2014). Do you have any other books in the works?

But of course! I can’t say much about it now, but suffice it to say, like my previous two works, it’s one of those forgotten stories in American history. The two leading figures in this story are people everyone has heard of, a pair of antagonists who have been both loved and hated throughout the years. It’s the story of their decades-long public and private war, a tale that is alternately hilarious and harrowing. Stay tuned!

I first heard of this about ten years ago, and I was shocked that I had never heard of this. I also live in Michigan and read a lot of true crime accounts.

Excellent interview, and I totally agree with Bernstein: Kehoe was not motivated solely by stress caused by taxes. To me, it is very telling that he did everything he could to destroy his farm, including cutting down all the fruit trees and propping them up on stumps using wire so no one would realize and stop him, but also so no one could ever farm the land. This was an extremely angry man, driven to destroy.